How will the cities of the future be supplied with fresh, high-quality food in a sustainable way? It takes about 2,300 m2 of cropland to feed one person for a year, equivalent to 10 m2 of cropland per each square metre of the city. Producing food is energy-intensive and relies today mainly on fossil sources of energy. As populations increase and cities grow, we shall need new ways of producing food in a sustainable way, to counteract the exploding consumption of land and energy. Part of the solution is to produce food where it is consumed.

Growing vegetables in cities

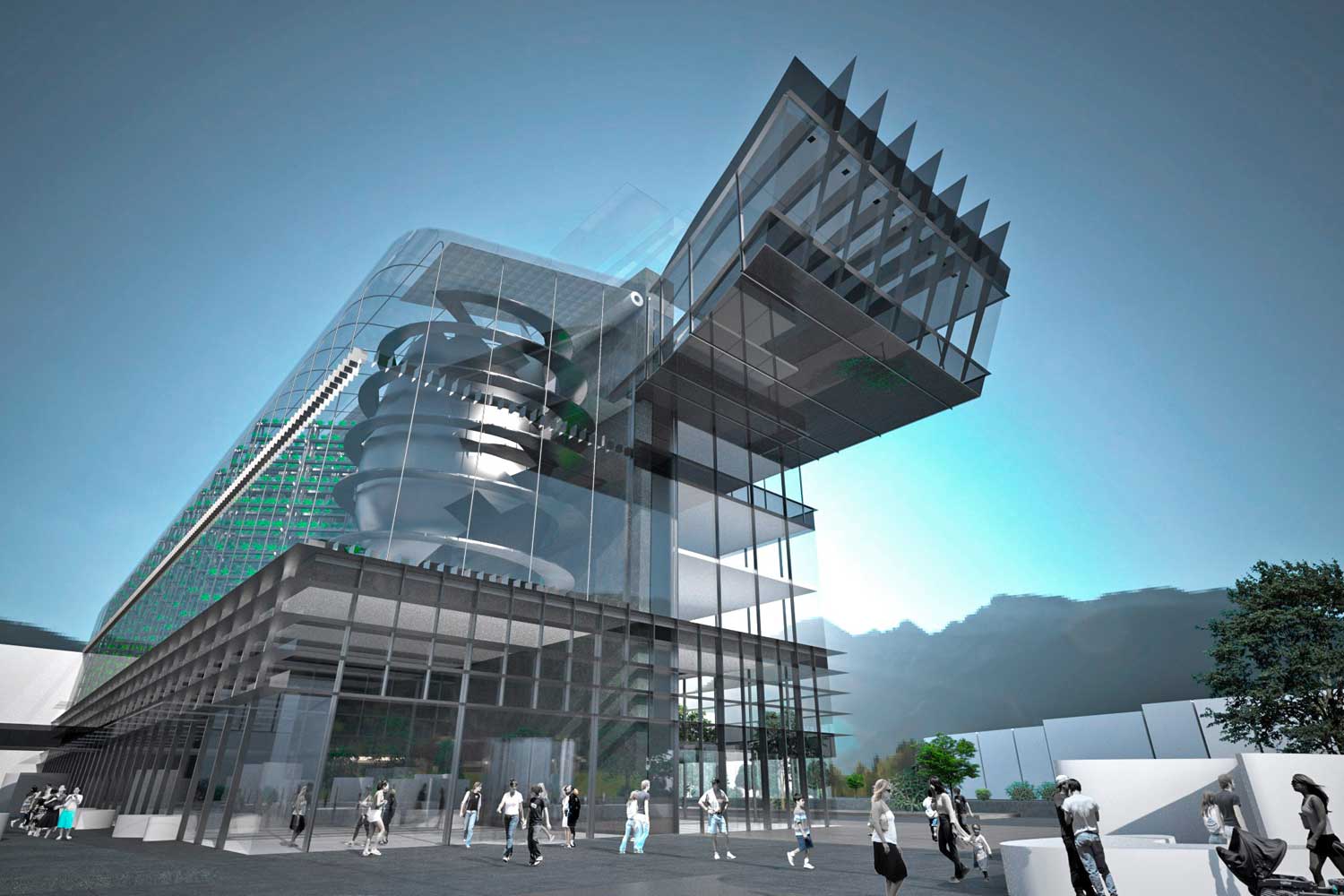

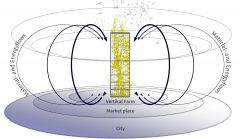

Vertical farming is a pioneering technique of producing food locally in densely built-over areas. Cultivating crop plants arranged vertically could help to reduce the area of land needed to produce food for cities and to make cities more energy-efficient overall. Vertical farming buildings are closed systems in which fresh products are cultivated in stacks with various different methods of production. Yields from levels one above the other can be higher than from a comparable area on the ground.

Several climate zones develop in these vertical stacks, and the distribution of daylight is not uniform; so suitable conditions for different crops can be created in a confined space throughout the year. However, state-of-the-art technology is essential for this. To achieve energy and resource-efficient production, the various cycles of use must be adjusted to each other and fine-tuned.

Space and energy requirements

Recent research findings show that vertical farming leads to drastic reductions in land use. Theoretically, one square metre of ground can be used for a large multiple of this area. Per square foot of vertical farm area, 50 square foot of cropland outdoors could be replaced. Vertical farming needs energy for light, warmth and cooling. The aim is to operate the farms with renewable sources of energy, thus achieving a closed cycle. Energy consumption can be reduced if suitable crop plants are combined and suitable crop rotation sequences are developed.

If the type of building and the plants selected do not match properly, though, energy consumption will be far too high and it will not be possible to cover requirements with renewable sources of energy. For instance, it turns out that it does not make sense to provide artificial light for tomatoes in a vertical farm, even if ultra-efficient LEDs are used.

R&D for the vertical farm

In Austria the trailblazer in this sector is the vertical farm institute, that is linked in an international research network. In Austria it works on feasibility studies for vertical farms. In an exploratory project the fundamentals for developing a prototype vertical farm for Vienna are currently being worked out; here the vertical farm institute is collaborating with the Institute of Buildings and Energy at Graz University of Technology, the Department of Crop Sciences at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna, and with SIEMENS as a partner from industry. Issues to do with plant physiology and types of architecture are being investigated, the potential of climatic conditions analysed and answers to questions in the fields of building, communications and control engineering found. The aim is to develop a hybrid building design combining vertical farming with accommodation and office use. The important question here is to what extent the energy flows involved in these three functions can complement each other, and how large the resulting synergies are. www.verticalfarminstitute.org

„We stand for food production within urban spaces, independent from fossil fuels. With vertical farms we see the possibility not only to reduce the consumption of resources but also to close energy loops. Regional, organic products have to be produced next to the consumer. Food production within cities will become a part of daily urban life again.“

Daniel Podmirseg

CEO, vertical farm institute